Finding Binary & Decimal Palindromes

Recently I’ve had my 33rd birthday and since I’m a nerd I also checked the binary representation of that number, which is 100001.

OMG, I thought to myself, 33 is a palindrome in both bases! I immediately checked when my next palindromtastic birthday would be:

99

That’s a tad over my life expectancy, but arguably reachable. After that, the numbers get big quite fast. Exponentially fast. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences has an entry for the sequence of these numbers, with a list of the 147 known elements (at the time of writing this post). The largest known number is 9335388324586156026843333486206516854238835339 with 46 decimal and 153 binary digits. That’s quite large indeed.

Life is short, let’s spend what little we have on finding even bigger palindromes!

Method

Naturally, I didn’t know which algorithm would be the most effective before running any code. In order to quickly iterate over algorithm prototypes, I used python and only switched to a more performant language (Rust) and optimised after the algorithm stabilised. It is tempting to do all kinds of low-level optimisations as you go, but these make the code more complex and have a far lower benefit than improving the algorithm, since in this problem, working less is orders of magnitude more efficient than working faster.

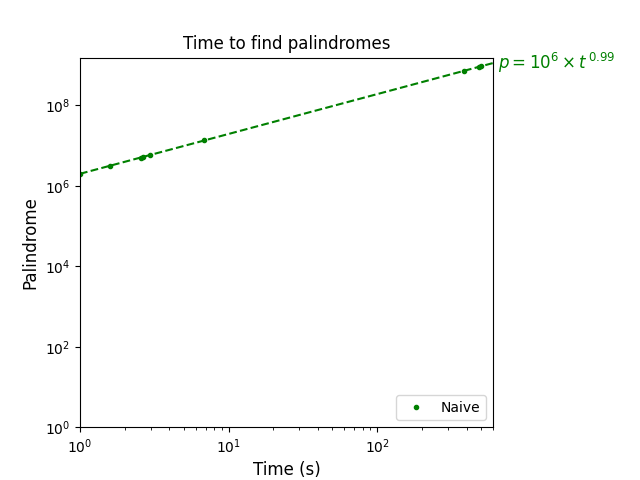

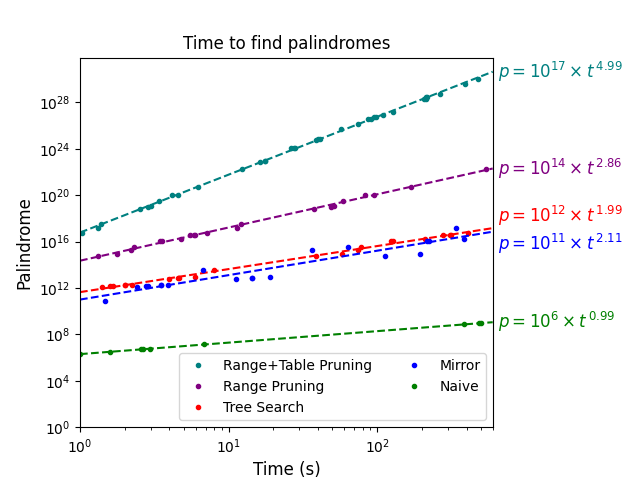

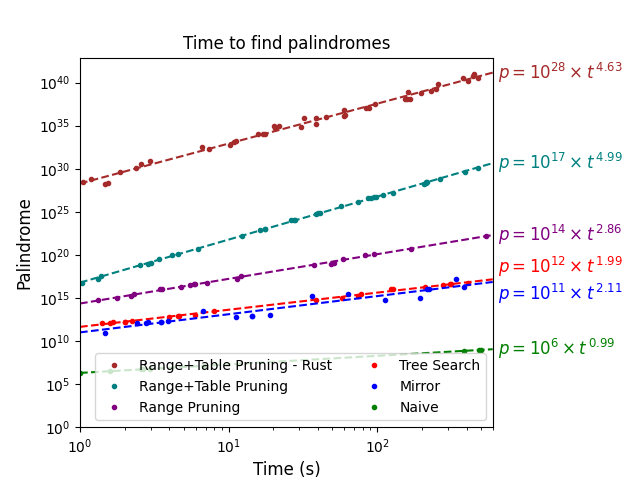

I compared the performance of different algorithms by letting them run for 10 minutes and recording when each palindrome was found. The results were then plotted on a graph with logarithmic scales and a curve of the form \(p=b \times t^a\) was fit to the data. In a log-log scale, this type of curve appears as a line with a slope of the exponent \(a\). With the equation, we can estimate the time needed to go through all known palindromes and start finding new ones, by solving it for \(p=\)9335388324586156026843333486206516854238835339.

While a brief glance at the list of known palindromes gives the impression that they grow exponentially, we can also show that with some back-of-the-envelope math and hand-waving. Feel free to skip to the next section if you wish, this won’t be in the test.

The probability of a number \(k\) to be a palindrome is the chance of its left half being equal to its right half. Each of the halves has roughly \(\sqrt{k}\) possible values, and for each value of the left half, there’s only one value of the right half that is equal to it. This means that the probability of the two being equal is roughly \(1/\sqrt{k}\). Note that the above is independent of base.

Assuming (what is possibly not true, but we’ll do it anyway) that the probability of being a palindrome in base 10 and the probability of being a palindrome in base 2 are independent, the probability of both being true is simply \(1/k\). According to this, the number of palindromes that are smaller or equal to some number \(n\) would be \(\sum_{k = 0}^{n}1/k\). This is the sum of the harmonic series, which increases like \(\ln{n}\). If the palindrome’s index behaves like the logarithm of the number, the number behaves like the exponent of the index, hence the exponential growth.

Naive approach

The most straightforward approach to the problem is simply to iterate over all numbers and check for each one whether it is a palindrome in both bases or not:

def check_if_palindrome(num):

bin_str = bin(num)[2:]

dec_str = str(num)

if bin_str == bin_str[::-1] and dec_str == dec_str[::-1]:

palindrome_found(num)

def main():

i = 1

while True:

check_if_palindrome(i)

i += 1

Results

Summary

- Biggest palindrome found: 939474939 (31st)

- Exponent of equation: 0.99

- ETA to new palindromes: 354883853472718214778068282638336 years

The results are not very interesting without any comparison, but there’s one important detail. The exponent of our approximate equation is very close to 1, which is hardly surprising, as our algorithm is clearly linear. If we would run it for twice as long, we would find palindromes twice as big (the actual number, not the number of digits).

According to the equation, it would take us around 354 nonillion (yes, I had to look that up) years before we start finding new palindromes, which is slightly more than I’m personally willing to wait. Seems like we have to find a more efficient algorithm.

Mirror approach

Instead of going through every number, we can only go through the decimal palindromes and check if each of them is a binary palindrome as well. Every even-lengthed palindrome can be constructed by taking a number, mirroring it and sticking the mirrored bit back on the original number.

For instance, the palindrome 123321 is 123 glued together with 321. For odd-lengthed palindromes we just need to drop a digit when glueing the numbers together: 12321 is 12 (123 without the last digit) glued together with 321.

So in order to iterate through all the decimal palindromes, we still iterate through every number, but instead of checking if the number is itself a decimal palindrome, we use the above method to create two decimal palindromes out of it:

def check_if_binary_palindrome(num):

bin_str = bin(num)[2:]

if bin_str == bin_str[::-1]:

palindrome_found(num)

def main():

i = 1

while True:

check_if_binary_palindrome(int(str(i) + str(i)[::-1]))

check_if_binary_palindrome(int(str(i)[:-1] + str(i)[::-1]))

i += 1

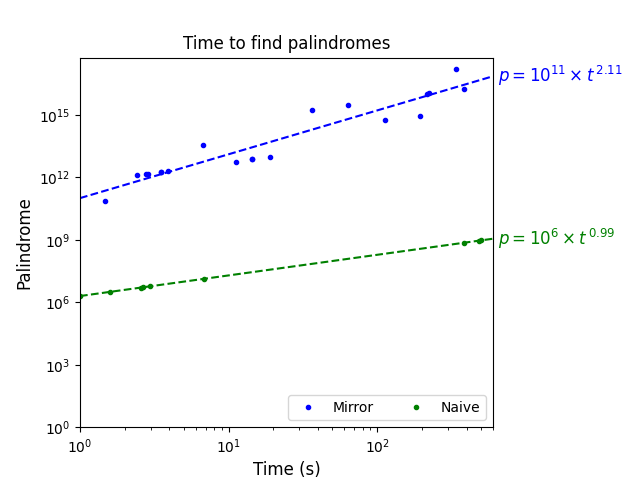

Results

Summary

- Biggest palindrome found: 18279440804497281 (57th)*

- Exponent of equation: 2.11

- ETA to new palindromes: 1267197148 years

We can immediately see that this time the results do not lie so neatly near the line. This happens because the algorithm interleaves the search for adjacent odd and even lengths.

The actual biggest palindrome found using the mirror approach is the 63rd one, 313558153351855313, with 18 digits, but due to the nature of the algorithm some earlier elements, with 17 digits, were not found before the 10 minutes ran out.

This algorithm has found roughly twice as many palindromes as the naive one and the exponent of its approximate equation is somewhat close to 2. This is because we’re only checking a square root of all numbers, making our algorithm quadratic.

Tree search

That was a significant improvement, but obviously, we want to be even faster, which means doing even less work. For this, we are going to remodel the problem as a series of tree searches. Each such search is only looking for palindromes of a given decimal length.

In the tree, the root is empty and children are created by adding a digit on the right of the contents of their parent. For instance, the number 23 has 10 children - the numbers 230 to 239. The root is a special case since it only has 9 children - we don’t want numbers with 0 as their most significant digit.

Notice that the \(n\)-th layer of this tree (starting with the root on layer 0) contains all the numbers of decimal length \(n\).

In the search for a palindrome of decimal length 6, we can do a depth-first-search up to a depth of 3 to generate all 3-decimal-digit numbers, and from them all 6-decimal-digit palindromes. The same process can be done for any other length \(n\), by going up to depth \(\lceil n/2 \rceil\).

This search can be implemented using recursion in the following way:

def find_palindromes(current_digits, decimal_length):

if len(current_digits) * 2 >= decimal_length:

left_half = current_digits[:decimal_length - len(current_digits)]

decimal_palindrome = int(left_half + current_digits[::-1])

check_if_binary_palindrome(decimal_palindrome)

return

if len(current_digits) == 0:

next_digits = range(1, 10)

else:

next_digits = range(10)

for next_digit in next_digits:

new_digits = current_digits + str(next_digit)

find_palindromes(new_digits, decimal_length)

def main():

decimal_length = 1

while True:

find_palindromes("", decimal_length)

decimal_length += 1

The motivation for this change is that now we can add logic to exclude entire parts of the tree as we go through it if we know that they contain no binary palindrome. For instance, the most significant bit of all binary palindromes is 1 (it can’t be 0, and there is no other option), so the least significant bit must also be 1, making all binary palindromes odd. All odd numbers have an odd least significant decimal digit, and if they are palindromic, the same digit is their most significant decimal digit.

In other words, the most significant decimal digit of all binary-decimal palindromes has to be one of 1,3,5,7,9 and we can adjust our code accordingly, changing:

if len(current_digits) == 0:

next_digits = range(1, 10)

to:

if len(current_digits) == 0:

next_digits = range(1, 10, 2)

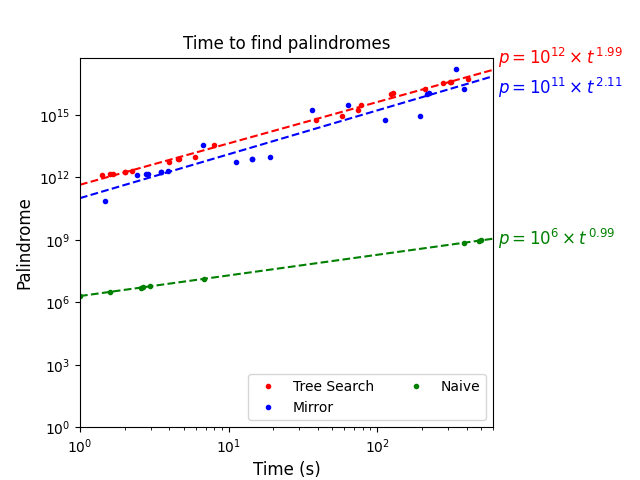

Results

Summary

- Biggest palindrome found: 161206152251602161 (62nd)

- Exponent of equation: 1.99

- ETA to new palindromes: 6128843749 years

Our results here are arguably better than the previous version, but it’s hardly significant. The exponent is closer to 2 since the errors are far smaller.

This lower exponent causes our estimated time to increase almost five-fold to 6128843749 years, but that’s only due to having a better estimation, our new algorithm is not worse.

Range pruning

The cool thing about the above pruning is that it can be generalised to more than just the first bit/digit. I’ve learned in school (and probably you have as well) that a number is divisible by 4 if its two least significant decimal digits form a number that is divisible by 4. For instance, we know that 123456 is divisible by 4 since 56 is. What I haven’t learned in school is that this is also true for the remainder from division by 4: 1234567 mod 4 = 67 mod 4 = 3. This works because 100 is divisible by 4, and so are all higher powers of 10, so any change to decimal digits higher than the least significant 2, only changes the number in multiples of 4 - leaving the remainder unchanged.

Similarly, the remainder of any number from division by 8 is equal to the remainder from the division of just the 3 least significant digits. That’s because 1000 is divisible by 8. This continues with 16, 32, 64,…,2\(k\), requiring 4, 5, 6,…,\(k\) digits respectively. In binary representation, the remainder from dividing by 2\(k\) is simply the \(k\) least significant bits.

In the context of our search, this means that once we know the \(k\) least (and most) significant decimal digits of a decimal palindrome, we also know its \(k\) least (and most) significant bits if it is also a binary palindrome.

At every step as we go down the tree, our node determines the range of palindromes we will generate under it. If the decimal length of the palindrome is 7 and we are in the node containing the number 35, all the decimal palindromes we will generate below this node are in the range [3500053, 3599953]. The 2 least significant bits in 53 are 01, therefore we know that we are looking for a binary palindrome of the form 10…01.

All numbers in the range [3500053, 3599953] have 22 bits, so we know that we are looking for a binary palindrome of the same length, specifically, one in the range [1000000000000000000001b, 1011111111111111111101b] = [2097153, 3145725]. Here is where it gets interesting, the ranges do not overlap! Therefore no decimal palindrome in that range is also a binary palindrome, and we can prune the entire subtree under 35 from our search.

If not all numbers in the range have the same length in bits, we do not prune, as this scenario doesn’t happen often enough to justify more complicated code.

In python, it looks like this:

def is_pruned(decimal_digits, decimal_length):

middle_decimal_length = decimal_length - 2 * len(decimal_digits)

min_decimal_palindrome = int(decimal_digits + "0" * middle_decimal_length + decimal_digits[::-1])

max_decimal_palindrome = int(decimal_digits + "9" * middle_decimal_length + decimal_digits[::-1])

binary_length = min_decimal_palindrome.bit_length()

if max_decimal_palindrome.bit_length() != binary_length:

return False

binary_digits = bin(min_decimal_palindrome)[-len(decimal_digits):]

middle_binary_length = binary_length - 2 * len(binary_digits)

min_binary_palindrome = int(binary_digits[::-1] + "0" * middle_binary_length + binary_digits, 2)

max_binary_palindrome = int(binary_digits[::-1] + "1" * middle_binary_length + binary_digits, 2)

return min_binary_palindrome > max_decimal_palindrome or max_binary_palindrome < min_decimal_palindrome

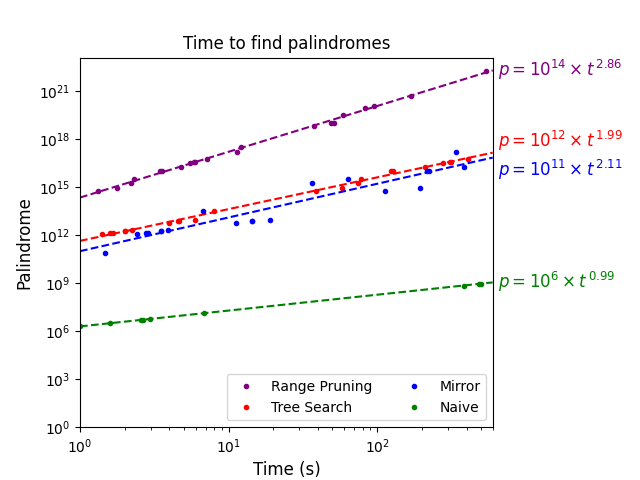

Results

Summary

- Biggest palindrome found: 17461998948684989916471 (71st)

- Exponent of equation: 2.86

- ETA to new palindromes: 3534 years

The shiny new exponent of 2.86, shows the huge significance of pruning.

The time estimate for finding new palindromes might still be the tiniest bit over the desired number but it’s no longer in the ludicrous zone. Assuming a 100-fold improvement after optimisations, this turns into an entirely feasible 35 computer years. For comparison, the Seti@home project managed to crowdsource over two million years of computing time. Nevertheless, it’s still not time to start optimising, as there’s still one card left in the sleeve.

Table pruning

The range pruning method is using the knowledge of the least significant bits. This time, let’s look at the most significant bits.

Let’s say we are searching for a palindrome with a decimal length of 9, and our search has arrived at the node 755. Our decimal range is [755000557, 755999557] = [101101000000000110010011101101b, 101101000011111010001101000101b]. If we pay attention to the binary representation, we can notice that the two bounds share the 10 most significant bits - 1011010000, therefore all numbers in that range start with these 10 bits as well.

If any binary palindrome lies in this range, its 10 least significant bits must be also the same bits, but in reverse order, so we know it would look like this: 1011010000??????????0000101101 where “?” represents unknown bits.

Now let’s subtract the lower decimal bound from this hypothetical palindrome in both bases (we will soon see why):

_ 1011010000??????????0000101101 _ 755???557 _ hypothetical_palindrome

101101000000000110010011101101 755000557 lower_decimal_bound

0000000000??????????1101000000 ???000 result

These are the exact same calculations, just in different bases, therefore both results should represent the same number. There are 3 unknown decimal digits, but we know that the left one and the right one are equal since they are the centre digits of a palindrome. In total, this adds up to 10x10=100 possible numbers, and if we go through all of them we would notice that none end with the bits 1101000000.

If the bottom lines in our calculation are not equal, we’ve reached a contradiction. As before, the conclusion is that no binary-decimal palindrome lies under the node 755, and we can prune that entire subtree.

The key insight is that since the 755 and 557 in the bound turned to zeros in the result of the subtraction, the 100 possibilities for ???000 are independent of the node 755. They are the same for every node where only two digits are left to be chosen in the tree of palindromes with 9 decimal digits. That means we could create a lookup table of the least significant bits of these numbers before starting the search and reuse it throughout the search for a palindrome of that length.

In later searches with more decimal digits, it will be useful to create tables of sizes 1000, 10000, etc. for when 3, 4 or more digits respectively are left to be chosen.

In python, this translates into another pruning function:

def is_pruned_by_table(min_decimal_palindrome, max_decimal_palindrome, lookup_table):

nonshared_bits_length = (max_decimal_palindrome ^ min_decimal_palindrome).bit_length()

shared_most_significant_bits = bin(min_decimal_palindrome >> nonshared_bits_length)[2:]

hypothetical_least_significant_bits = int(shared_most_significant_bits[::-1], 2)

subtraction_result = hypothetical_least_significant_bits - min_decimal_palindrome

subtraction_least_significant_bits = subtraction_result % (1 << len(shared_most_significant_bits))

return not is_in_table(subtraction_least_significant_bits, len(shared_most_significant_bits), lookup_table)

Implementing the table in a compact way that still keeps is_in_table relatively efficient is not trivial, but this post will not get into the details, as it’s already long enough.

Results

Summary

- Biggest palindrome found: 1115792035060833380605302975111 (95th)

- Exponent of equation: 4.99

- ETA to new palindromes: 195 hours = Slightly over 8 Days

As the exponent rises to almost 5, the ETA plummets to a very comfortable zone, albeit a little too optimistic. While in 10 minutes, the lookup tables still don’t fill the memory of the computer, with higher numbers we can expect to hit this limit. Not being able to create big-enough tables will reduce the efficiency of the algorithm the longer it runs.

Optimisation

Finally, it is time to optimise. We rewrite the algorithm in Rust, stop using strings everywhere and add parallelism. This is a good opportunity to praise the Rust language and its ecosystem with crates such as rayon and once_cell making parallel programming delightfully easy.

Results

Summary

- Biggest palindrome found: 38090421176450233778487733205467112409083 (130th)

- Exponent of equation: 4.63

- ETA to new palindromes: An hour and 50 minutes

While the increase in speed is ludicrous, the lower exponent shows the decreasing efficiency of the algorithm due to the inability to make big-enough tables.

Seems like we’re ready!

New Results

Running the optimised program for about two weeks, 29 new palindromes were found. 28 of which are elements 148-175 in the series, up to a decimal length of 53. In addition, due to parallelism, one palindrome with a decimal length of 55 was found, whose index is a mystery.

Without further ado:

148 12328899531897059171731113717195079813599882321

149 16422159001061376847917371974867316010095122461

150 36755925874534219715185758151791243547852955763

151 56243939994005432191600400619123450049993934265

152 72224512737657344148643434684144375673721542227

153 72830033748815722240681118604222751884733003827

154 74953152103456169263148284136296165430125135947

155 78737696079148631316169196161313684197069673787

156 102735644379963218861031130168812369973446537201

157 502186653128032879493361163394978230821356681205

158 597817365870480462496846648694264084078563718795

159 1873893355166996611906735376091166996615533983781

160 7109242970502610649115178715119460162050792429017

161 9142687306518774468290258520928644778156037862419

162 128426799107797312365090999090563213797701997624821

163 308714513290492817327216515612723718294092315417803

164 349755095251390482672234414432276284093152590557943

165 544889901625422417825862090268528714224526109988445

166 546590550388169569066255343552660965961883055095645

167 1671376559622765380050133113310500835672269556731761

168 1894500919149741184783894664983874811479419190054981

169 3329456979344803072321377337731232703084439796549233

170 11583408501354096073227429192472237069045310580438511

171 14290800261309297950160720602706105979290316200809241

172 38042682015138742476430662826603467424783151028624083

173 74107193679989476350632192529123605367498997639170147

174 96974333658798698186600459595400668189689785633347969

175 98269568061626490790443471917434409709462616086596289

??? 1610250372237506394572456221226542754936057322730520161

Update (2023)

A few more numbers found with the program, including the index of the aforementioned mystery palindrome:

176 141608322140499819558130089980031855918994041223806141

177 1610250372237506394572456221226542754936057322730520161

178 5375810570128326670426378465648736240766238210750185735

179 5500130929952642025961499398939941695202462599290310055

180 5750352680855632597679040581850409767952365580862530575

181 5982107767230157388234011419141104328837510327677012895

182 7992515739300692681583388637368833851862960039375152997

183 9794258529088310956256765905095676526590138809258524979

Epilogue

This problem is a great example of the importance of using the right tool for the job. When trying to find really big palindromes, our bottlenecks are CPU time and RAM, therefore we require a good algorithm implemented in a performant language. When trying to find that good algorithm, however, our bottlenecks are developer time and creativity, so for this task, we need a language that minimises the time between having a new idea and finishing its implementation.

Zooming in on the algorithm, its improvement required a drastic reduction of the number of decimal palindromes checked. Remodelling the problem as a tree search surely added some overhead, but it also gave us many opportunities to skip whole groups of decimal palindromes.

When I started working on this, I didn’t know (and I still don’t) how the first 147 elements were found, so I hope this post serves as a convenient starting point for you to come up with your own algorithms that will find even bigger palindromes in a fraction of the time.

All of my code can be found here: palindromes

Finally, I would like to take the opportunity to wish my grandma, who celebrates her 99th (1100011b) birthday this month, a very happy and palindromtastic birthday! :)