Finding Evidence for GPL Violation with Ghidra and Friends

Let’s say you’ve worked a few years on an open source project released under the GNU General Public License (GPL)

and let’s say you’ve spied an application that is eerily similar to your project but whose owner claims no infringement of your rights.

How would you find evidence for such infringement or lack thereof?

Obviously, I don’t know the answer to this question as it will vary depending on your case.

I can, however, tell what I did when faced with this situation, which I hope you will find educational or even entertaining.

This post is somewhere between a write-up and a tutorial. Hopefully it is interesting as both.

Hang on to your trousers, we’re going in!

Ingredients

- An open source project on which you’ve worked for the past few years, released under a copyleft license such as the GPL.

- Some rascal who released a highly suspicious proprietary application that might contain code from your project.

- PEid

- OllyDbg

- Ghidra

Background

Since 2015 I’ve been a maintainer of the Spring RTS Engine project. During this time I’ve written some code, got into many heated arguments and introduced quite a few bugs. All in all, I had a lot of fun and I highly recommend getting involved in open source projects.

Part of the charm is that you have to learn new things all the time, because if you don’t do something, it’s quite probable no one else will. A game engine developer investigating an alleged GPL violation is a good example for this.

A few months ago we’ve discovered a newly released proprietary game - [MARS] Total Warfare (will be referred to as MARS from now on) that looked and felt extremely similar to games based on Spring.

These similarities weren’t limited to look-and-feel but also included technical characteristics, such as using similar assets and containing a lua scripting engine with the exact same API up to the Spring.Foo() calling convention.

The download itself is a small <6MB executable, but every time the game is started it “streams” (read: downloads) a few dozen MBs of assets that can be found here.

In this script, for instance, you can find a number of function calls (Spring.Echo(...), Spring.IsCheatingEnabled(), Spring.SendMessageToPlayer(...)) conveniently described in Spring’s documentation.

In fact this script was originally written for Spring games but now is used within MARS. This can be explained by one of two options:

- The developer of MARS recreated Spring’s lua API, asset loading code etc. without using Spring’s source. This is not entirely improbable, after all Spring itself started as a clone of the 1997 game Total Annihilation.

- The developer of MARS used Spring’s source code while making MARS without releasing the code of MARS, in violation of the GPL.

How can we distinguish between the two? The easiest way is to just ask the dev!

Alas, we have to delve into the executable and compare it with Spring’s.

Scouting

The easiest things to look for are strings, just fire up your favourite hex editor or viewer and search for them.

In our case, since MARS implements Spring’s lua API which mostly looks like Spring.FunctionName(), we can expect to find both "FunctionName" and "Spring" in the binaries.

How could this be? We know for sure that the game uses these strings.

A voice in the back of your head has a suggestion: The executable might be packed!

But why would someone want to shave a few MB off of an executable when it downloads a few dozen more every single time it starts?

Might it be that they wanted to hide something? But let us not rush into conclusions which will present themselves in due time on their own accord.

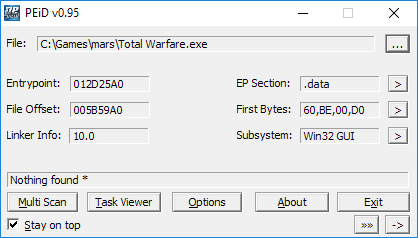

PEid to the rescue! It should tell us what packer was used, so we can unpack the executable and start working already!

Wait! There’s “Extra Information”!

What this means is that while we don’t know which packer was used, statistical analysis shows that the entropy is higher than expected for a normal executable (Spring’s entropy, for instance, is 6.26). This makes a lot of sense, in a non-packed executable there are many strings, there are instructions which are more common and ones which are less, so the distribution is less flat => the entropy is lower.

While we don’t know the packer, we do know of a program that unpacks this executable - the executable itself! It must unpack the packed instructions into memory before the CPU can execute them, so all we need to do is run it and then dump the memory where the unpacked instructions reside. For this we use OllyDbg.

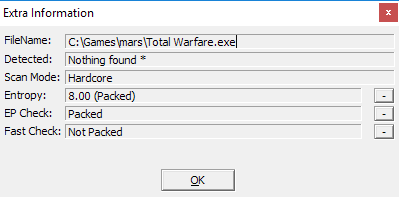

We start the game, we start OllyDbg and we attach it to the game’s process. If we are already running unpacked code, we should be able to see this in the call stack:

We can see that the code being ran is between offsets 0x017XXXXX-0x01BXXXXX so let’s look where these reside in the memory map:

Voilà! We’ve found a good candidate - note how it has E (execute) permissions which is exactly what we would expect. Can we find our strings inside?

Time to dump this segment (Right-Click->Backup->Save data to file…) and press on forward.

Don’t forget to write down the base address of this segment (OllyDbg automatically appends it to the file’s name), we will need it very soon.

You can also close the game and delete it now, unless you want to play it, but do you, really?

Raiding

It is now time to bring the big guns. We will use Ghidra to reverse engineer the segment we’ve just dumped. Fire Ghidra up, import the file and make sure you set the base address in the options to the one you have written down.

Now double click the file and let Ghidra analyse it. While it’s analysing feel free to go for a walk, play a set of tunes on your accordion, put the kettle on and/or skim the front page of reddit. This takes some time.

Our foot-in-the-door here is the lua API. If you want to expose a C function to lua code, it will be done more or less like this:

lua_pushstring(L, functionName);

lua_pushcclosure(L, functionPointer, 0);

lua_rawset(L, -3);So if we search for functionName we should find a reference to it from the glue code, and right under it we should find the pointer to the function itself!

Follow the XREF to find something familiar:

In the right you can see the decompiled code, it’s not always 100% accurate, but it’s surprisingly good.

We can now rename functions to make the code easier to read. Bonus points if you change the signature of lua_rawset so it shows -3 instead of 0xfffffffd.

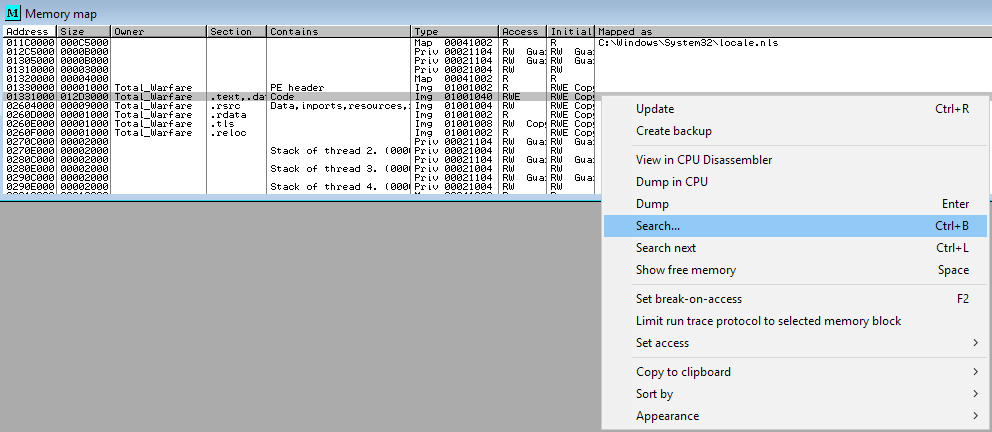

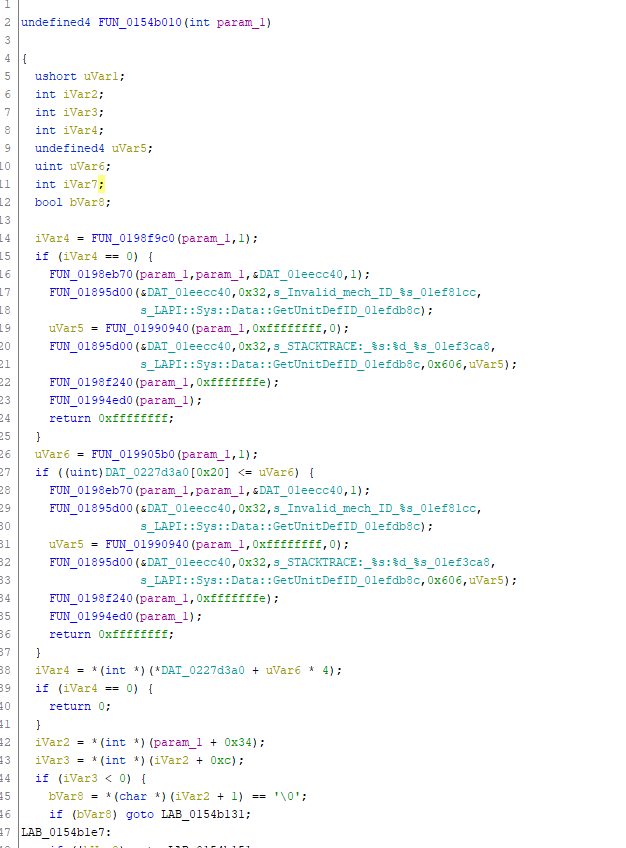

As we planned before, we now follow LAB_0154b010 where we expect to find Spring.GetUnitDefID(). When we get there, press F to create a function.

Making heads or tails from this code might have been hard if not for the fact we have a reference! In Spring this function gets the unique ID of an ingame unit from lua, checks whether the lua state asking for its type (unitDef) is allowed to have this information and if it is, returns the ID of the unitDef to lua. Like homework, reverse engineering becomes much easier when you have the solution in front of you. We expect to see something similar to:

int LuaSyncedRead::GetUnitDefID(lua_State* L)

{

CUnit* unit = ParseUnit(L, __func__, 1);

if (unit == nullptr)

return 0;

if (IsAllyUnit(L, unit)) {

lua_pushnumber(L, unit->unitDef->id);

} else {

if (!IsUnitTyped(L, unit))

return 0;

lua_pushnumber(L, EffectiveUnitDef(L, unit)->id);

}

return 1;

}Most of the differences can be explained by the inlining of ParseUnit(), IsAllyUnit(), etc. so we will use them as reference as well.

static inline CUnit* ParseRawUnit(lua_State* L, const char* caller, int index)

{

if (!lua_isnumber(L, index)) {

luaL_error(L, "[%s] unitID (arg #%d) not a number\n", caller, index);

return nullptr;

}

return (unitHandler->GetUnit(lua_toint(L, index)));

}

static inline CUnit* ParseUnit(lua_State* L, const char* caller, int index)

{

CUnit* unit = ParseRawUnit(L, caller, index);

if (unit == nullptr)

return nullptr;

// include the vistest for LuaUnsyncedRead

if (!IsUnitVisible(L, unit))

return nullptr;

return unit;

}Well, that’s weird… In Spring’s code we have one input error message but MARS has two? Maybe they’re not related?

Hold your horses, Who said MARS based itself on the latest version? Let’s go a little bit back in time to 2015:

static inline CUnit* ParseRawUnit(lua_State* L, const char* caller, int index)

{

if (!lua_isnumber(L, index)) {

if (caller != NULL) {

luaL_error(L, "Bad unitID parameter in %s()\n", caller);

} else {

return NULL;

}

}

const int unitID = lua_toint(L, index);

if ((unitID < 0) || (static_cast<size_t>(unitID) >= unitHandler->MaxUnits())) {

if (caller != NULL) {

luaL_error(L, "%s(): Bad unitID: %d\n", caller, unitID);

} else {

return NULL;

}

}

return (unitHandler->GetUnit(unitID));

}

static inline CUnit* ParseUnit(lua_State* L, const char* caller, int index)

{

CUnit* unit = ParseRawUnit(L, caller, index);

if (unit == NULL) {

return NULL;

}

return IsUnitVisible(L, unit) ? unit : NULL;

}Now that looks much more similar! Let’s rename things accordingly in the decompiled code:

We now continue to IsUnitVisible and the rest

static inline bool IsAllyUnit(lua_State* L, const CUnit* unit)

{

if (CLuaHandle::GetHandleReadAllyTeam(L) < 0) {

return CLuaHandle::GetHandleFullRead(L);

}

return (unit->allyteam == CLuaHandle::GetHandleReadAllyTeam(L));

}

static inline bool IsUnitVisible(lua_State* L, const CUnit* unit)

{

if (IsAllyUnit(L, unit)) {

return true;

}

return !!(unit->losStatus[CLuaHandle::GetHandleReadAllyTeam(L)] & (LOS_INLOS | LOS_INRADAR));

}

static inline bool IsUnitTyped(lua_State* L, const CUnit* unit)

{

if (IsAllyUnit(L, unit)) {

return true;

}

const unsigned short losStatus = unit->losStatus[CLuaHandle::GetHandleReadAllyTeam(L)];

const unsigned short prevMask = (LOS_PREVLOS | LOS_CONTRADAR);

if ((losStatus & LOS_INLOS) ||

((losStatus & prevMask) == prevMask)) {

return true;

}

return false;

}Here is the decompiled, renamed and annotated code (I’m not sure if it’s entirely correct, but that doesn’t matter much)

int GetUnitDefID(int L) {

...

luaStateContext = *(int *)(L + 0x34);

readAllyTeam = *(int *)(luaStateContext + 0xc);

if (readAllyTeam < 0) {

noFullRead = *(char *)(luaStateContext + 1) == '\0';

if (noFullRead) goto LAB_0154b131;

LAB_0154b1e7:

if (!noFullRead) goto LAB_0154b151;

if (noFullRead) goto LAB_0154b185;

unitDefID = *(int *)(unit + 0x218);

if (!noFullRead) goto LAB_0154b1b1;

}

else {

sameAllyTeam = readAllyTeam == *(int *)(unit + 0xac);

if (!sameAllyTeam) {

LAB_0154b131:

/* 3 = LOS_INLOS | LOS_INRADAR */

if ((*(byte *)(*(int *)(unit + 0x28c) + readAllyTeam * 2) & 3) == 0) {

return 0;

}

if (readAllyTeam < 0) {

noFullRead = *(char *)(luaStateContext + 1) == '\0';

goto LAB_0154b1e7;

}

sameAllyTeam = readAllyTeam == *(int *)(unit + 0xac);

}

if (sameAllyTeam) {

LAB_0154b151:

lua_pushnumber(L,(float)*(int *)(*(int *)(unit + 0x218) + 8));

return 1;

}

if (sameAllyTeam) {

unitDefID = *(int *)(unit + 0x218);

if (sameAllyTeam) goto LAB_0154b1b1;

}

else {

LAB_0154b185:

losStatus = *(ushort *)(*(int *)(unit + 0x28c) + readAllyTeam * 2);

/* 0xc = LOS_PREVLOS | LOS_CONTRADAR */

if (((losStatus & 1) == 0) && ((losStatus & 0xc) != 0xc)) {

return 0;

}

unitDefID = *(int *)(unit + 0x218);

if (readAllyTeam < 0) {

if (*(char *)(luaStateContext + 1) != '\0') goto LAB_0154b1b1;

}

else {

if (readAllyTeam == *(int *)(unit + 0xac)) goto LAB_0154b1b1;

}

}

}

/* is decoy */

if (*(int *)(unitDefID + 0x13c) != 0) {

unitDefID = *(int *)(unitDefID + 0x13c);

}

LAB_0154b1b1:

lua_pushnumber(L,(float)*(int *)(unitDefID + 8));

return 1;

}We can see the following things (check comments in code):

- MARS uses lua contexts to save visibility permissions about the lua state in the exact same way as Spring. A boolean value controls whether the state has fullread (can see everything) and a number represents the team (allyteam in Spring jargon) this lua state belongs to (basically limiting it to see what the player can see). If the state has fullread, the allyteam number will be negative.

- MARS is saving the line of sight status of units in the exact same way as Spring. A packed bitfield contains flags such as INLOS, PREVLOS and CONTRADAR. The tests whether a unit’s unitDef is known are identical to Spring’s.

- MARS is handling decoys (units that appear to be a different unit to the enemy) in the exact same way as Spring.

This should be enough to convince us we’re not entirely paranoid. It’s unlikely MARS was coded using clean-room design. One might say, however, that the lua API is insignificant, coding it according to the documentation is quite straightforward and the similarities are inevitable.

Alright, we can look for some inner function, something that exists not only as part of the lua API.

Attacking

Our candidate is Spring.GetUnitsInRectangle().

By now you should be able to find it, look for a reference and rename some vars to get this:

int GetUnitsInRectangle(undefined4 L)

{

...

lua_checkfloat2_3(mins,L,1,2);

lua_checkfloat2_3(maxs,L,3,4);

allegiance = FUN_01546330();

GetUnitsExact(local_54,mins,maxs);

local_8 = 0;

lua_createtable(L,0,0);

count = 0;

/* AllyUnits = -3 */

if (allegiance == -3) {

/* loop and push units */

}

else {

/* EnemyUnits = -4 */

if (allegiance == -4) {

/* loop and push units */

}

else {

/* MyUnits = -2 */

if (allegiance == -2) {

/* loop and push units */

}

else {

/* AllUnits = -1 */

if (allegiance < 0) {

/* loop and push units */

}

else {

isAllied = IsAlliedTeam(L,allegiance);

if (isAllied == 0) {

/* loop and push units */

}

else {

/* loop and push units */

}

}

}

}

}

...

return 1;

}Seems very similar to:

int LuaSyncedRead::GetUnitsInRectangle(lua_State* L)

{

const float xmin = luaL_checkfloat(L, 1);

const float zmin = luaL_checkfloat(L, 2);

const float xmax = luaL_checkfloat(L, 3);

const float zmax = luaL_checkfloat(L, 4);

const float3 mins(xmin, 0.0f, zmin);

const float3 maxs(xmax, 0.0f, zmax);

const int allegiance = ParseAllegiance(L, __FUNCTION__, 5);

#define RECTANGLE_TEST ; // no test, GetUnitsExact is sufficient

vector<CUnit*>::const_iterator it;

const vector<CUnit*> &units = quadField->GetUnitsExact(mins, maxs);

lua_newtable(L);

int count = 0;

if (allegiance >= 0) {

if (IsAlliedTeam(L, allegiance)) {

LOOP_UNIT_CONTAINER(SIMPLE_TEAM_TEST, RECTANGLE_TEST);

} else {

LOOP_UNIT_CONTAINER(VISIBLE_TEAM_TEST, RECTANGLE_TEST);

}

}

else if (allegiance == MyUnits) {

const int readTeam = CLuaHandle::GetHandleReadTeam(L);

LOOP_UNIT_CONTAINER(MY_UNIT_TEST, RECTANGLE_TEST);

}

else if (allegiance == AllyUnits) {

LOOP_UNIT_CONTAINER(ALLY_UNIT_TEST, RECTANGLE_TEST);

}

else if (allegiance == EnemyUnits) {

LOOP_UNIT_CONTAINER(ENEMY_UNIT_TEST, RECTANGLE_TEST);

}

else { // AllUnits

LOOP_UNIT_CONTAINER(VISIBLE_TEST, RECTANGLE_TEST);

}

return 1;

}But that’s to be expected. What we actually want to investigate is how GetUnitsExact() is implemented.

While the lua API has to be quite similar, games that were developed separately will have subtly different ways of finding out which units reside inside a map rectangle.

To see what differences exist, we can compare Spring’s method (reference) with other open source strategy games such as 0AD (reference) and OpenRA (reference). All examples use the same general idea:

- Partition the map into a grid of squares (quads in Spring jargon).

- For each square keep a list of units in that square.

- When queried about a map rectangle, check which squares intersect with the given rectangle and return all units within them.

But there are also implementation differences:

- The square size (Spring: 128, 0AD: 20, OpenRA: 1024). Obviously that also depends on the scale of the game, but having an identical size should raise an eyebrow or two.

- The method of iterating over the squares. Both OpenRA and 0AD go with the straightforward way of calculating the max. and min. row and column of squares intersecting the rectangle, then doing a triple loop over row/col/unit. Spring (for some arcane reason) calculates the max. and min. row and column just the same, but instead of doing a triple loop, it does two double loops. In the first it iterates over row/col and populates a list of squares. In the second it iterates over <squares_in_list>/units.

- Since units in Spring have a radius, they can exist in more than one square. This requires a system for preventing duplicates.

Here is Spring’s code:

std::vector<int> CQuadField::GetQuadsRectangle(const float3& pos1, const float3& pos2) const

{

...

std::vector<int> ret;

const int maxx = std::max(0, std::min((int(pos2.x)) / quadSizeX + 1, numQuadsX - 1));

const int maxz = std::max(0, std::min((int(pos2.z)) / quadSizeZ + 1, numQuadsZ - 1));

const int minx = std::max(0, std::min((int(pos1.x)) / quadSizeX, numQuadsX - 1));

const int minz = std::max(0, std::min((int(pos1.z)) / quadSizeZ, numQuadsZ - 1));

if (maxz < minz || maxx < minx)

return ret;

ret.reserve((maxz - minz) * (maxx - minx));

for (int z = minz; z <= maxz; ++z) {

for (int x = minx; x <= maxx; ++x) {

ret.push_back(z * numQuadsX + x);

}

}

return ret;

}

std::vector<CUnit*> CQuadField::GetUnitsExact(const float3& mins, const float3& maxs)

{

...

const std::vector<int>& quads = GetQuadsRectangle(mins, maxs);

/* Initialize current color */

const int tempNum = gs->tempNum++;

std::vector<CUnit*> units;

std::vector<int>::const_iterator qi;

for (qi = quads.begin(); qi != quads.end(); ++qi) {

std::list<CUnit*>& quadUnits = baseQuads[*qi].units;

std::list<CUnit*>::iterator ui;

for (ui = quadUnits.begin(); ui != quadUnits.end(); ++ui) {

CUnit* unit = *ui;

const float3& pos = unit->midPos;

/* Unit already colored so can be skipped */

if (unit->tempNum == tempNum) { continue; }

if (pos.x < mins.x || pos.x > maxs.x) { continue; }

if (pos.z < mins.z || pos.z > maxs.z) { continue; }

/* Color the unit */

unit->tempNum = tempNum;

units.push_back(unit);

}

}

return units;

}The two double loops and the list of quads are immediately visible. The next thing that grabs your eye is tempNum - the duplicates prevention mechanism. In short, every unit that was inserted to the returned vector is coloured with a unique colour (a running global counter). Units that have the current colour must have been already added and are therefore skipped.

Time to check MARS. We will start with GetQuadsRectangle():

void GetQuadsRectangle(void *this,float *mins,float *maxs,undefined4 param_3,int **out_quads)

{

iVar6 = *(int *)((int)this + 0x580);

maxx = ((int)(((uint)((int)*maxs >> 6) >> 0x19) + (int)*maxs) >> 7) + 1;

if (iVar6 < maxx) {

maxx = iVar6;

}

if (maxx < 0) {

maxx = 0;

}

iVar9 = *(int *)((int)this + 0x584);

maxy = ((int)(((uint)((int)maxs[2] >> 6) >> 0x19) + (int)maxs[2]) >> 7) + 1;

if (iVar9 < maxy) {

maxy = iVar9;

}

if (maxy < 0) {

maxy = 0;

}

minx = (int)(((uint)((int)*mins >> 6) >> 0x19) + (int)*mins) >> 7;

if (iVar6 < minx) {

minx = iVar6;

}

if (minx < 0) {

minx = 0;

}

miny = (int)(((uint)((int)mins[2] >> 6) >> 0x19) + (int)mins[2]) >> 7;

if (iVar9 < miny) {

miny = iVar9;

}

if (miny < 0) {

miny = 0;

}

if ((((miny <= maxy) && (minx <= maxx)) && (numRows = (maxy - miny) + 1, miny <= maxy)) &&

(ptr = *out_quads, minx <= maxx)) {

rowsDone = 0;

numCols = (maxx - minx) + 1;

numPairs = (int)((numCols >> 0x1f) + 1 + (maxx - minx)) >> 1;

do {

while( true ) {

if (numPairs == 0) {

pairsDone = 1;

}

else {

uVar5 = 0;

do {

uVar4 = uVar5;

*ptr = *(int *)((int)this + 0x588) * miny + minx + uVar4 * 2;

ptr = *out_quads;

*out_quads = ptr + 1;

ptr[1] = *(int *)((int)this + 0x588) * miny + minx + 1 + uVar4 * 2;

uVar5 = uVar4 + 1;

ptr = *out_quads + 1;

*out_quads = ptr;

} while (uVar5 < numPairs);

pairsDone = uVar4 + 2 + uVar5;

}

if (numCols <= pairsDone - 1U) break;

rowsDone = rowsDone + 1;

iVar9 = *(int *)((int)this + 0x588) * miny;

miny = miny + 1;

*ptr = iVar9 + minx + -1 + pairsDone;

ptr = *out_quads + 1;

*out_quads = ptr;

if (numRows <= rowsDone) {

return;

}

}

rowsDone = rowsDone + 1;

miny = miny + 1;

} while (rowsDone < numRows);

}

return;

}In the start we can see the standard clamping of mins and maxs together with the conversion from world coordinates to row and column.

This conversion is simply coord >> 7 or in other words coord / 128.

At this moment in time your eyebrow should be in a raised position.

For some code generation and/or compilation reason, it looks like we have three nested loops, but that’s only because it’s populating the square (quad) vector two squares at a time which requires dealing with an odd number of columns.

Ultimately, this function does the exact same thing as Spring’s GetQuadsRectangle().

Onwards to GetUnitsExact():

undefined4 __thiscall GetUnitsExact(void *this,undefined4 param_1,float *mins,float *maxs)

{

...

cVar1 = FUN_01437cb0();

if (cVar1 == '\0') {

quadVectorStart = (int *)FUN_01376f60(0);

quadVectorEnd = quadVectorStart;

GetQuadsRectangle(this,mins,maxs,&quadVectorStart,&quadVectorEnd);

tempNum = gsTempNum;

gsTempNum = (undefined4 *)((int)gsTempNum + 1);

currentQuadPtr = quadVectorStart;

while (currentQuadPtr != quadVectorEnd) {

local_30 = FUN_01ce6990(*currentQuadPtr);

FUN_01cf0310(this,*currentQuadPtr,1);

local_8 = 1;

FUN_013c3f90(&local_2c);

while( true ) {

FUN_013c3fc0(&local_2c);

cVar1 = FUN_013c3fa0(&local_2c);

if (cVar1 == '\0') break;

ppfVar2 = (float **)FUN_013c3fe0();

local_24[0] = *ppfVar2;

/* check maxs, mins and tempNum */

if (((((undefined4 *)local_24[0][0xb9] != tempNum) &&

(local_28 = local_24[0] + 0x3f, *mins < *local_28 || *mins == *local_28)) &&

(*local_28 < *maxs || *local_28 == *maxs)) &&

((mins[2] < local_24[0][0x41] || mins[2] == local_24[0][0x41] &&

(local_24[0][0x41] < maxs[2] || local_24[0][0x41] == maxs[2])))) {

*(undefined4 **)(local_24[0] + 0xb9) = tempNum;

/* push unit */

FUN_0152f6a0(local_24);

}

FUN_013c3fd0();

}

local_8 = 0;

FUN_01cf03a0();

currentQuadPtr = currentQuadPtr + 1;

}

}

else {

/* Nearly the same as the previous if,

with the exception of a different

global for initializing tempNum */

}

*in_FS_OFFSET = local_10;

return param_1;

}Even though the decompilation isn’t entirely coherent, the structure is clear. There are two nested loops in the same structure as Spring, first on the quad vector and then on the units within the quad. The same method (tempNum) is used to prevent duplicates.

The main difference is the branching of the external if according to the result of FUN_01437cb0().

This might be necessary if our function is called from another function that uses tempNum or if two such functions can run in parallel.

Probably one of the changes to Spring made by the MARS developer.

To conclude:

- MARS uses the same square size as Spring.

- MARS has the same (non-standard) two double-nested loops implementation as spring for checking which units are in a given map rectangle.

- MARS uses the same colour (tempNum) mechanism for preventing duplicates.

Winning

This was enough to convince me that MARS was not coded using clean-room design and it is very likely that its developer copied and adapted code from Spring.

I hope it was enough to convince you as well.

Since the sources of MARS weren’t released and since the developer denied the above, I fear that it is knowingly in violation of the GPL.

It’s important to say that the Spring community is very happy that Spring is used in many projects (commercial or otherwise) and the best outcome in our opinion would be a source code release of MARS.

Thank you for reading!